“Naturally, I do not know the future but I do know that for one brief moment in history there was the San Francisco Cannabis Buyers’ Club … and it was about love.” – Dennis Peron, July 25, 1995

By the time the people of California voted to legalize medical marijuana, the man who spearheaded the initiative had been raided, arrested, and shot by police. He’d been harassed, intimidated, and manipulated. As the face of the medical marijuana movement, he’d become a political target and martyr.

When Proposition 215, also known as The Compassionate Use Act, passed on November 5th, 1996, Dennis Peron, the self-professed “gay hippy outlaw” who “legalized marijuana in response to the AIDs crisis,” was facing charges of criminal conspiracy, possession and transportation of marijuana. That August, he’d been forced to close The Cannabis Buyers’ Club, California’s first dispensary.

He’d been sidelined on his own initiative months earlier, when billionaire activist George Soros put his weight and resources behind the cause. Bill Zimmerman, a Soros appointee, would ultimately take credit for 215’s passage. Peron had lead legalization efforts in the state for decades, and now, as California prepared to make history, everyone from President of the United States to his own political allies were determined to make him a footnote in his own story.

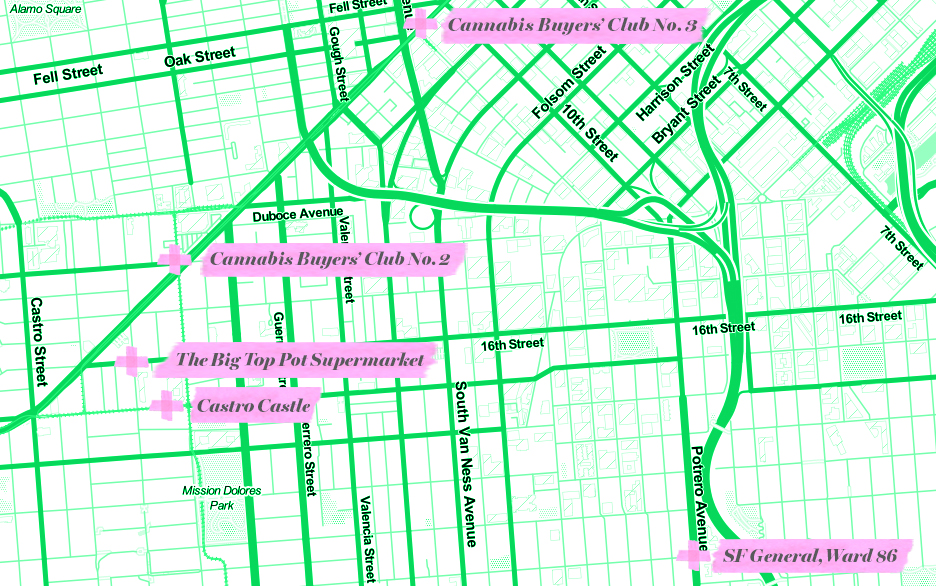

Peron had been slinging weed in San Francisco since he left the Air Force in 1969, first in the city’s communes and later in more formal venues. His future ambitions took shape at the aptly named Big Top Pot Supermarket, which supplied weed to patrons of The Island, Peron’s fully illegal Amsterdam-style café. The Island became a sort of queer political hub, eventually operating as early campaign headquarters for California’s first openly gay elected official, Harvey Milk, among others.

At the time, medical marijuana wasn’t even part of the conversation. Instead, Peron used his political connections to push for comprehensive legalization. Then AIDS hits.

“We lived a dream, collecting food stamps, tripping in the park, with free love every night, sharing our lovers as well as our lives,” Peron wrote in his Autobiography.

Like so many queer people, Peron watched friends and lovers die in waves, and his fight for legalization evolved. Following the death of his lover, Jonathan West, Peron dedicated his life to the legalization of medical marijuana. With the help of friends like Brownie Mary Rathbun, an elderly waitress who became a disarming figurehead for the cause, and John Entswistle, Peron’s partner and political comrade, he would open the Cannabis Buyers’ Club. At its peak, the Club occupied a five-story building in downtown San Francisco and served as campaign headquarters for Prop 215.

On November 5th, 1996, the people of California voted to legalize medical marijuana, but California’s first dispensary was under attack. That August, the Cannabis Buyers’ Club was raided. The police seized more than 40 pounds of pot, and Peron vowed not to reopen until after the November election. He kept that vow, but was arrested again in October.

It was the beginning of a new era and the beginning of the end for the Cannabis Buyers’ Club, which, under a new name, was ordered closed in 1998 by a San Francisco Supreme Court judge. That year, Peron moved to a farm near Clear Lake, California, a little over 100 miles north of San Francisco, where he created a cooperative grow operation. He eventually returned to the city, where he and Entwistle ran a bed and breakfast out of their home.

Peron died in January 2018, the same month that Proposition 64 made recreational marijuana legal in California. He strongly opposed that initiative, holding until the end that “all use is medical.” The days of freely providing weed to the sick and dying were dead. The CBC and its way of doing business were history.

The Cannabis Buyers’ Club would grow to 8,000 members, but at the time, it was just a publicity stunt, a way to take the cause to the courts.

In the years since Peron left the city, San Francisco has become a playground for Silicon Valley elites and the face of a national housing crisis. Queer spaces have been replaced by craft beer bars and experimental yoga studios. As the resurfacing of the city continues, we risk losing the history of those spaces and the people that lived in them.

In an attempt to preserve Peron’s legacy, The Grass Agency has created a tour of his San Francisco; we enlisted our close friend, the enormously talented florist, Tyson Lee, to create a bouquet in celebration of the very queer history of legalization; and we spent one windy day photographing it in front of the many places that Peron transformed.

Today, Dennis Peron’s San Francisco is nearly unrecognizable. If you look closely, though, you can still catch glimpses of the city that he loved, a place full of hope and compassion, where the weed is free and so are the people.

The Big Top Pot Supermarket

3499 16th St.

Peron landed in San Francisco in 1969, and almost immediately fell into the hippy life. He spent the next few years selling weed out of The Big Top, a commune that eventually housed 28 people.

“We lived a dream, collecting food stamps, tripping in the park, with free love every night, sharing our lovers as well as our lives,” Peron wrote in his Autobiography, Memoirs of Dennis Peron: How a Gay Hippy Outlaw Legalized Marijuana in Response to the AIDS Crisis.

But all good things must come to an end. In 1974, The Big Top was raided and Peron ended up serving six months of modified jail time. Not one to let a little time served deter him, he signed a lease on an empty building at the corner of Sanchez and 16th St. that same year. With the help of some friends, he turned the space into The Island (a reference to Aldous Huxley’s utopian novel), a hotbed and veritable hotbox for political action. As Peron put it, “The Island was the only restaurant in the world where pot smoking was nearly mandatory.” He kept his patrons supplied in the stuff through The Big Top Supermarket just upstairs.

The Supermarket would move from atop the Island to an 11-room flat on Castro St. and Peron would eventually put down roots in a Victorian on 17th St., now known as The Castro Castle. As the Big Top’s footprint grew, so did the threat of police intervention. In 1977, Peron was busted again. It was during this Big Top raid that Peron was shot in the leg by an officer who later said that he’d wished he’d killed him, so there would be “one less faggot in San Francisco.”

The Island closed after two and a half years, and a string of restaurants would open in its place. Today, 3499 16th St. is home to Kitchen Story, a casual Asian-fusion brunch spot, serving french toast and mimosas to the double-wide stroller set.

San Francisco General Hospital, Ward 86

995 Potrero Ave.

The 1960s and 70s saw the Castro transformed from a working class enclave into a gay haven.

Peron described the neighborhood at the time as “a powerful alternative culture scene, a central nexus chock full of ‘freaks and fairies.’” Gay men from all over the country were migrating to San Francisco and spaces like The Island served as beacons of hope in a country hostile to homosexuals.

When the 80s rolled around, gay neighborhoods like the Castro would undergo another, more violent transformation. An unknown disease, eventually identified as AIDS, swept through the queer community, turning once safe spaces into epicenters of suffering. Thousands of gay and trans people died in those early days, and activists like Peron and Mary Rathbun (aka Brownie Mary) quickly mobilized. Early treatments for the disease had strong side effects, and marijuana proved to be a formidable antidote.

In 1983, San Francisco General Hospital, which now bears the name of Facebook CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, opened the country’s first dedicated HIV clinic, now known as Ward 86. This is where Rathbun got her name, passing out pot brownies to AIDS patients, many of whom wouldn’t make it out of the hospital alive. As the AIDS epidemic continued, Mary and Peron would become close allies in the fight to legalize medical marijuana, providing safe and free weed to the people who needed it most.

Today, a trip to Ward 86 is no longer a death sentence. The city has seen a dramatic decrease in the number of AIDS-related fatalities and San Francisco General’s pioneering HIV clinic has continued to lead the way.

The Castro Castle

3745 17th St.

Just around the block from Kitchen Story, sits the Castro Castle, a four-story Victorian with a fake rock facade interrupted by a psychedelic shock of rainbow waves on its garage doors. From the mid-80s until his death last year, this Castro landmark served as home to Peron and his partner, John Entwistle, who co-authored Prop 215. For a number of years, the pair ran the four-story home as a Bed and Breakfast, giving boarders a place to rest where the Cannabis Buyers’ Club was born.

When police raided the Castle on January 27th, 1990, Peron’s then lover, Johnathan West, was suffering from full-blown AIDS. The police confiscated four pounds of weed and Peron was thrown in jail. West would later testify in court that the marijuana was his and that he was using it as medicine. The charges were dropped and West died two weeks later, spurring Peron to action.

In effect, West’s death gave birth to California’s first dispensary and, eventually, Prop 215. For the next four years, Peron and his allies would focus on making medical marijuana accessible to the people who needed it most. Peron would join Brownie Mary, bringing cannabis to AIDS patients, he would spearhead local and state-level legislation, and, by chance, become the founder of the Cannabis Buyers’ Club.

The Cannabis Buyers’ Club would grow to 8,000 members, but at the time, it was just a publicity stunt, a way to take the cause to the courts. Peron, Brownie Mary, and their comrades reasoned that the quickest way to make medical marijuana accessible was through the courts and the easiest way to get there was by breaking the law. They anticipated the media attention, inviting a camera crew to cover the opening of “Brownie Mary’s Cannabis Café,” a fabricated dispensary for AIDS patients setup in Peron’s basement. What they didn’t anticipate was how quickly it would blossom into the real thing.

After the story aired, the phone started ringing off the hook. There was real demand for a real cannabis café, and soon after, the Cannabis Buyers’ Club took shape. From the time it was conceived in 1993, the Club would move from Dennis’ basement to a small, second-floor apartment on the corner of Ford and Sanchez. It soon outgrew the space, and in April 1994, the Buyers’ Club moved to a 2,000 sq ft. flat above the Transfer, a popular gay bar. Media attention was growing and so was the Club’s membership.

Cannabis Buyers’ Club No. 2

194 Church St.

“The new location was a dream come true in which we finally had room to realize our ambitions and while secret in the technical sense, the word was out, people could find us. And they did,” Peron wrote in his autobiography.

The Cannabis Buyers’ Club was hiding in plain sight, and while the police had yet to come knocking, patients of all ages, with their own specific needs came pouring in. There were people with glaucoma, cancer, epilepsy, arthritis and a hose of other ailments, and The Buyers’ Club was there to serve them. According to Peron, the Church St. location ultimately served close to 2,000 patients, offering 10 different types of flower, a variety of baked goods, and extracts. It became a community space and a hub of political action. As the Club’s membership grew, Peron and his colleagues continued the push to legalize medical marijuana. Despite support in Congress, however, bill after bill stalled at the governor’s desk. Having failed to pass a bill, they took another tack, beginning the process of a ballot initiative. If Peron and his allies could gather 800,000 signatures in 150 days, they’d be able to put legalization to a vote in the 1996 general election.

Still, the Cannabis Buyers’ Club was going strong. Peron set his sights on an even larger space at 1444 Market St., right on the edge of San Francisco’s financial district. The Cannabis Buyers’ Club abandoned its Church St. location in 1995, the same day its founding members filed the original text for Prop 215. 194 Church St. would eventually play host to another medical marijuana dispensary, and finally, a full-service events space called The Office.

Cannabis Buyers’ Club No. 3, The Brownie Mary Rathbun Building

1444 Market St.

The Cannabis Buyers’ Club officially opened its doors on Market St. September 29th, 1995. Peron and a cadre of creatives turned the space into a weed wonderland, covering its walls in pot-leaf murals and establishing a political office on the mezzanine. That night, they celebrated the dedication of the space as the “Brownie Mary Rathbun Building,” but the party wouldn’t last long. A little over a year later, Attorney General Dan Lungren would begin his fatal assault on the Cannabis Buyers’ Club.

As Peron and his allies worked to put Prop 215 on the ballot, Lungren and a small group of law enforcement agencies were building a case against them. The medical marijuana movement was gaining momentum, but there were still big detractors in high places, chief among them, the President of the United States. The lead up to the general election proved a contentious time.

Peron had overestimated the reach of the Buyers’ Club. With just two months left to gather the remaining 700,000 signatures, billionaire activist George Soros stepped in through his surrogate, Bill Zimmerman.

The Compassionate Use Act would make it onto the ballot for the 1996 general election and pass with 5,382,915 votes on November 5th, 2016, but there was no saving California’s first dispensary. On August 4th, 1996, some three years after Peron and friends staged “The Brownie Mary Cannabis Café” in an attempt to bait law enforcement, the cops raided 1444 Market St. Peron was arrested three months later, and despite the passage of 215, the Buyers’ Club was forced to close its doors in 1998.

Peron then left the city to start a cannabis cooperative at a farm in Northern California, telling the SF Gate, that he’d grown tired of the city, but he would return. When he died in 2018, he and his then-husband, John Entwistle had reinvented The Castle as a bed and breakfast. The Castle, still stands today, a monument to a passionate and headstrong man who cared deeply about San Francisco and the people who chose to live here. If you happen to pass by at just the right time, you can still catch John walking his late husband’s dog around the block, past the original home of the Island, where it all began.

This story originally appeared in The Grass Guide on 06/25/19.